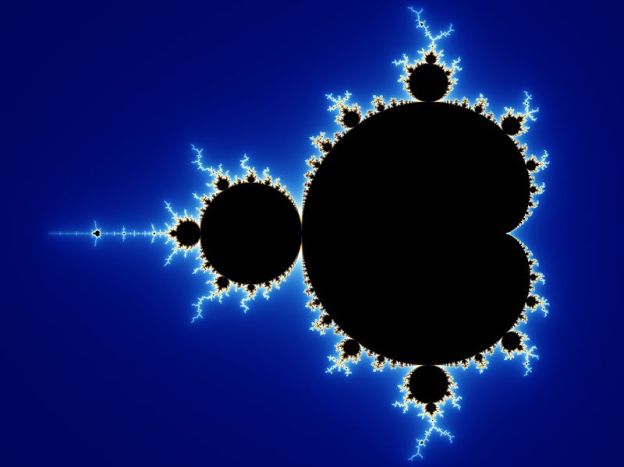

Fractals are a branch of math that better describes nature. Before fractals, there was Euclidean geometry, the geometry of lines, planes, and spaces. Euclidean geometry cannot give the length of a rough coastline; neither can it give the surface area of shaggy tree bark. The answer you arrive at in Euclidean geometry depends upon the scale at which you examine an object– intuitively the distance an ant travels over rough terrain is different from the distance we cover walking. The ant interacts with the terrain at a different length scale than we do. Fractal geometry is designed to handle objects with multiple meaningful length scales.

Fractal objects are sometimes called “scale-free“. This means that the object looks roughly the same even if examined at very different zooms. Many natural objects look similar at multiple zooms. Below, I include a few. The craters on the moon are scale-free. If you keep zooming in, you could not tell the scale of the image.

Terrain is often scale-free in appearance– a few years ago there was a joke photo with a penny for scale. The owners of the photo subsequently revealed that the “penny” was actually 3 feet across. I couldn’t find the photo, but you cannot tell the difference. The reveal was startling. Below is a picture of Mount St Helens. The top of this mountain is five miles (3.2ish km) away. Streams carry silt away from the mountain, as you can see more towards the foreground. They look like tiny streams. These are full-sized rivers. Mount St. Helens lacks much of the vegetation and features we would usually use to determine scale. The result is amazingly disorienting, and demonstrates scale invariance.

Plants are often scale free too. Small branches are very similar in appearance to large branches. Ferns look very fractal. Below is a picture of Huperzia phlegmaria. Each time this plant branches, there are exactly two branches. Along its length, it branches many times. It is a physical realization of a binary tree.

For more about fractals, read my posts about fractal measurement and the mandelbrot set.