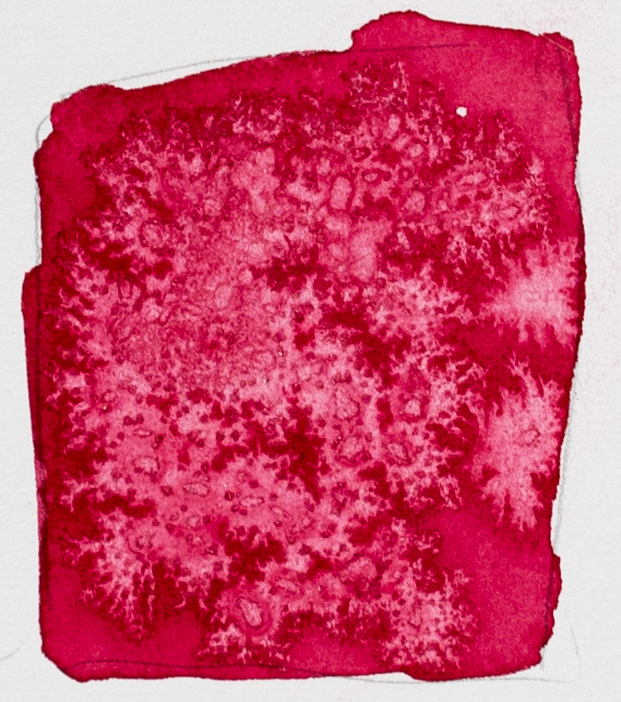

If you are interested in rail photography, or if you’re like me and really never gave it a thought, the O Winston Link photography museum in Roanoke, Virginia is a fascinating visit. O (short for Ogle– I think I’d go by the initial too) Winston Link photographed steam locomotives in the 1950s, at the very end of their widespread use. The Norfolk and Western rail lines he snapped ran through Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and other parts of the coal belt of Appalachia.

In his photographs, Link captures the end of a powerful technology, but he also captures life in 1950s Appalachian rail towns. People play in a pool twenty feet from a roaring locomotive. People read in their living room with a cat sleeping on their lap as a train passes the window. Folks chat on a porch as the N&W rolls past. In the image below, the train passes a drive-in movie.

Hotshot Eastbound, by O. Winston Link.

Link captured images with such technical precision that they would still be difficult shots today, barely possible without rare equipment until very recently. Link was a civil engineer, hired out of college as a photographer; during World War 2, he used his scientific and photographic backgrounds at the Airborne Instruments Laboratory.

Link’s railway shots rely heavily on both science and photographic techniques– in order to better control the lighting and thus the composition of his photos, he often shot at night. Because, he said, “I can’t move the sun — and it’s always in the wrong place — and I can’t even move the tracks, so I had to create my own environment through lighting.” This required the use of flash bulbs, one-use bulbs that burned metal to produce brief, intense illumination. According to the museum, one of his shots alone used illumination equivalent to 10,000- 100 watt light bulbs, although that light only lasted for a moment. Reading that, I wondered what the experience was like for the train conductor, driving through nearly black rural Virginia, when light so bright it might as well be lightning flashes. His first power source was too unreliable, and so he designed his own power source. Link invested $25,000 into the unpaid project, closer to $125,000 in today’s currency.

As someone who dabbles in photography, the difficulty of Link’s task and the quality of his work (60 years ago!) deeply impressed me. Bear with me as I explain some technical details of modern cameras to convey the awesomeness of Link’s work. Today, we might just be able to reproduce such shots without flashbulbs due to advances in digital photography. Flash bulbs (using combustion) are still brighter than any modern flash (using capacitors). A single flashbulb produced about 1 million lumens (the unit that measures the brightness of light) while a modern camera-mounted flash produces about 100,000. Many flashbulbs may be used at once, so the flashbulb is great for extreme illumination. Only one manufacturer of flash bulbs still exists. Their photo gallery is pretty neat.

Today, we have cameras that are more sensitive to low light, called high-ISO cameras. Camera speed, whether digital or film, is measured in a system called ISO-sensitivity. In this system, a film with double the ISO requires half the exposure time; a two-second exposure with 200 ISO film would take 1 second with 400 ISO film for the same level of exposure. In the 1950s, the fastest film was ISO 400-640. The Sony Alpha 7S, releasing in July, has up to ISO 409,600, 1024 times faster than ISO 400. A shot requiring 30 seconds of exposure on ISO 400 would require roughly 1/30 of a second on ISO 409,600. This is really new technology; as of 2013, no ISOs above 10,000 existed.

So, in short, Link’s work is a beautiful hybrid of science and art, a testament to their combined power. Link’s scenes of rural 1950’s Appalachian life are beautiful, and remind us of the era of the man behind the lens. New advances behind the lens are happening today. What new wonders will they capture?