In science, we tend only to learn about a small subset of the elements that populate our world. This is not unreasonable, since 96% of our bodies are composed of just hydrogen, water, carbon, and nitrogen. But there are over a hundred more elements, and they often influence life outside our bodies in ways we don’t hear about. So in today’s post I will talk about platinum.

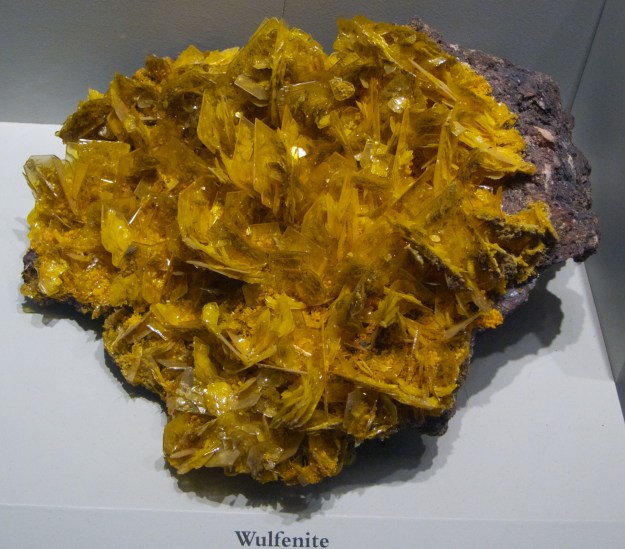

Platinum is one of the rarest metals in the Earth’s crust. Only 192 tonnes of it are mined annually, where 2700 tonnes of gold are mined annually. When the economy is doing well, platinum can be twice as expensive as gold. So what’s so valuable about it?

Platinum is used a lot in jewelry. Platinum has the appearance of silver, but it doesn’t oxidize and become tarnished like silver. It’s harder than gold, and its rarity can be appealing.

But it’s the chemical properties of platinum that set it apart. Platinum is a great catalyst. This means that platinum facilitates chemical reactions, but is not consumed as the reaction proceeds. The catalytic converter in your car is a platinum catalyst. The catalytic converter helps eliminate a variety of undesirable compounds such as carbon monoxide, nitrous oxides, and incompletely combusted hydrocarbons. Platinum is also a critical part of current hydrogen fuel cells; it splits hydrogen into protons and electrons.

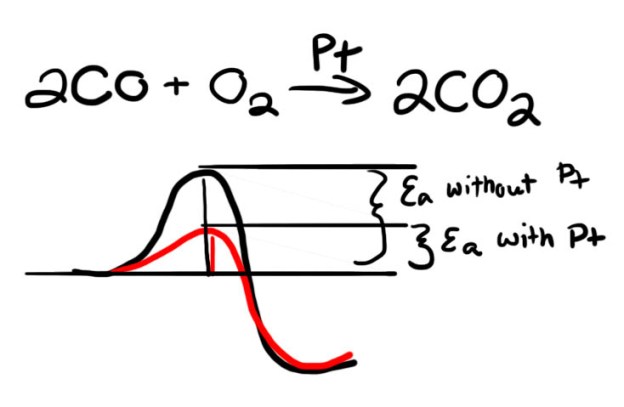

Platinum doesn’t force reactions to occur, but it makes them easier by reducing the energy required. The image below shows the reaction of carbon monoxide (CO) to carbon dioxide (CO2). The chart at the bottom shows the potential energy before, during and after the reaction. Imagine a ball rolling along the red curve (with platinum) and the black curve (without platinum). The ball on the black curve will need more speed to get over the hump. Any given ball is more likely to get over the red hump. Likewise, the presence of platinum lets CO get over the hump to become CO2. Platinum does this for all kinds of reactions.

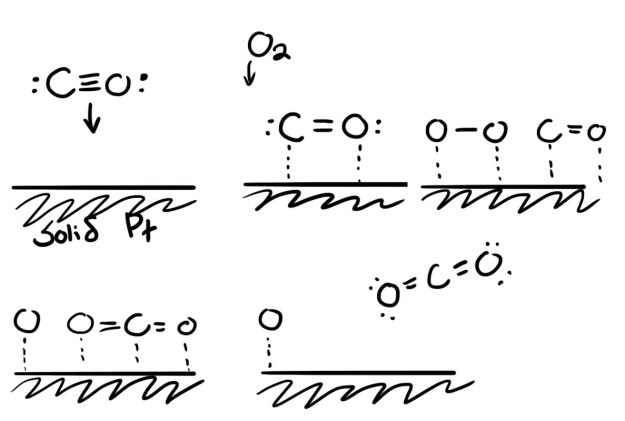

The reaction takes less energy because once a molecule bonds to the surface of platinum, the bonds within the molecule are a little weaker. Molecules like O-O and H-H can split into singletons, something they would never do off the surface. Below I show an example reaction for CO to CO2 on platinum. This diagram is meant to be illustrative, a possible mechanism for the reaction and to show how platinum helps out. In reality these reactions occur very quickly, and careers can be spent figuring out exact reaction mechanisms.

Platinum is a bit like velcro. Molecules become hooked to the surface, do their reaction, and unstick. If molecules stick and then refuse to unstick, this is called catalyst poisoning, and it’s a big issue in fuel cells. Like velcro, once the hooks are occupied, they can’t do anything else. Platinum is a good catalyst because a lot of things (like hydrocarbons) want to stick to it, but they don’t stick too hard. Other metals either are not attractive enough, or they are too attractive. Platinum is so valuable because, besides being rare, its properties happen to be balanced just right for the reactions we want.